On my 35th birthday last month, I decided to try something unconventional: I spent 30 minutes contemplating my own death.

I know how that sounds—morbid, depressing, perhaps even a bit unhinged. But this practice, known as memento mori ("remember that you will die" in Latin), has been embraced by philosophers, spiritual leaders, and artists for thousands of years across virtually every culture.

From Stoic philosophers to Bhutanese Buddhists, from Mexican Day of the Dead celebrations to the Islamic tradition of visiting cemeteries—humans have long recognized that regularly confronting our mortality doesn't diminish life but mysteriously enhances it.

What I discovered during that half-hour death meditation was both unsettling and clarifying. By the end, I felt a wave of unexpected emotions: gratitude, focus, and a strange, peaceful urgency.

The Art of Remembering Death

The Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote, "Let us prepare our minds as if we'd come to the very end of life. Let us postpone nothing. Let us balance life's books each day... The one who puts the finishing touches on their life each day is never short of time."

This isn't about being morbid. It's about using the most undeniable fact of existence—that it ends—as a tool for living well.

What makes memento mori so powerful is that it cuts through the layers of self-deception and distraction that normally insulate us from the stark reality of our finite time. When you genuinely confront the fact that you will die, many things that seemed important suddenly reveal themselves as trivial, while other neglected areas of life take on profound significance.

Death Awareness Across Cultures

What fascinates me about the practice of death awareness is its universality. Almost every wisdom tradition has discovered its clarifying power:

- Stoic philosophers kept death symbols on their desks to maintain perspective

- Zen Buddhists meditate in cemeteries as part of their training

- Bhutanese people traditionally think about death five times daily

- Ancient Egyptians displayed replicas of mummies at banquets

- Christian monks often kept skulls in their cells as reminders

The cross-cultural prevalence of these practices suggests they tap into something fundamental about the human condition. Despite our elaborate defenses against mortality awareness, part of us seems to recognize that confronting death enriches life.

The Science of Mortality Awareness

Modern psychology has begun to validate what ancient traditions intuited. Research on "mortality salience" (awareness of death) shows fascinating effects on human behavior and psychology.

Studies in the field of Terror Management Theory find that when people are subtly reminded of death, their values and behaviors change in predictable ways. Some become more defensive of their worldviews, while others show increased compassion and decreased materialism.

Most interestingly, research by Laura King and Joshua Hicks found that contemplating mortality in a mindful, philosophical context (rather than in fearful or traumatic circumstances) tends to increase:

- Appreciation for life's simple pleasures

- Commitment to meaningful personal goals

- Investment in close relationships

- Concern for leaving a positive legacy

What the ancients discovered through contemplative practice, science is now confirming: how we relate to death profoundly shapes how we experience life.

Three Modern Mortality Illusions

Despite these benefits, we modern people have become exceptionally skilled at avoiding death awareness. We've constructed three powerful illusions that shield us from confronting our mortality:

1. The Medical Illusion

Modern medicine's amazing capabilities have created the subtle impression that death is a technical problem to be solved rather than an intrinsic part of the human condition. Each medical advance pushes death further from our consciousness, making it seem like something that happens only due to insufficient intervention.

2. The Youth Illusion

Our culture worships youth while marginalizing the aging. We tuck the elderly away in retirement communities, use euphemisms like "passed away" instead of died, and market endless products promising to help us "stay young." This cultural architecture helps maintain the illusion that we personally might somehow be exempt from aging and death.

3. The Perpetual Tomorrow Illusion

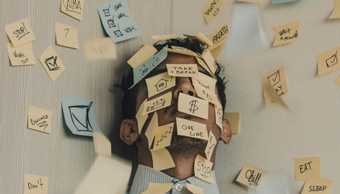

Perhaps most insidious is what psychologists call the "subjective immortality bias"—our tendency to intellectually acknowledge death while emotionally believing we always have more time. We perpetually defer our most meaningful aspirations to some future point, operating as if our time were infinite.

As the poet Mary Oliver asks: "Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?" The uncomfortable truth is that most of us respond with an implied "I'll figure that out tomorrow."

My Experiment with Memento Mori

After researching various death contemplation practices, I designed a simple 30-minute meditation for my birthday:

- I wrote my own obituary—first a conventional version, then an honest version

- I visualized my funeral, imagining what people might say and, more importantly, what they might leave unsaid

- I reflected on specific regrets I might have if I died within a year

- I contemplated the eventual dissolution of my body

- I meditated on the question: "What would I do differently if I had just received a terminal diagnosis?"

I won't pretend this was comfortable. It wasn't. But neither was it depressing. Instead, it created a remarkable clarity that persisted for days afterward.

Five Life-Changing Insights

The most valuable outcome of this practice has been five insights that continue to influence my daily choices:

1. Time Is Not Abstract

We typically think of time in abstract units—years, months, weeks. But when you vividly confront mortality, time transforms from an abstract concept into a precious, non-renewable resource.

I've started tracking my life in weeks using a simple grid where each row represents one year and each box one week of my life. Assuming an 80-year lifespan, I have about 4,160 weeks total. I've already used 1,820 of them. Seeing my remaining time represented visually has dramatically changed how I make decisions about where to invest my attention and energy.

2. Deathbed Regrets Are Predictable

When Australian palliative care nurse Bronnie Ware recorded the most common regrets of the dying, a clear pattern emerged. People rarely regretted career sacrifices or material pursuits. Instead, they regretted:

- Working too much and missing time with family

- Losing touch with friends

- Not expressing feelings honestly

- Not living authentically

- Not allowing themselves more happiness

What's striking is how predictable these regrets are, yet how commonly we make choices that virtually guarantee we'll have them.

3. Legacy Isn't What You Think

Contemplating my funeral revealed something important: the legacy we leave isn't primarily about achievements or creations. It's about how we affected the inner lives of others. Did we help others feel seen, understood, valued, and loved? Did we transmit wisdom, courage, or compassion that will outlive us?

This shifts the question from "What can I accomplish?" to "How can I positively influence the inner experience of those around me?"

4. You Can Die Before You're Dead

The philosopher Seneca observed that many people die at age 30 but aren't buried until age 80. Death awareness highlights that there are two ways to die: biological death and the slow death of disengagement, routine, and resignation.

This insight makes me regularly ask: Am I truly living, or am I just avoiding death? Am I growing and engaging fully with life, or am I merely existing?

5. Death Makes Life Meaningful

Perhaps most profound is the realization that death isn't opposite to a meaningful life—it's what makes life meaningful in the first place. In a universe where we lived forever, nothing would have urgency or significance. Every choice, every moment, every relationship derives its preciousness precisely from the fact that it will end.

As the Zen saying goes: "The trouble is, you think you have time."

The Weekly Memento Mori Practice

Based on my experience, I've incorporated a modified version of this practice into my weekly routine. Each Sunday evening, I spend 10 minutes on a simplified death meditation:

- I review my life-in-weeks grid and shade in another box

- I ask myself what I might regret if this were my last week

- I identify one action I can take in the coming week to live more in alignment with what ultimately matters

This brief practice serves as a reset button, preventing me from sleepwalking through too many precious weeks.

An Invitation, Not a Morbid Exercise

If any of this resonates with you, I invite you to try your own version of memento mori. This isn't about inducing anxiety or depression—it's about using our most fundamental truth to cut through the daily fog of triviality and distraction.

Start small: perhaps set aside 15 minutes this weekend to write a short reflection on what you would change if you knew you had only one year left. Notice how this thought experiment affects your perspective on current concerns and priorities.

As the Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius wrote in his private journal: "You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think."

What would you do differently if you took that insight seriously? I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments.